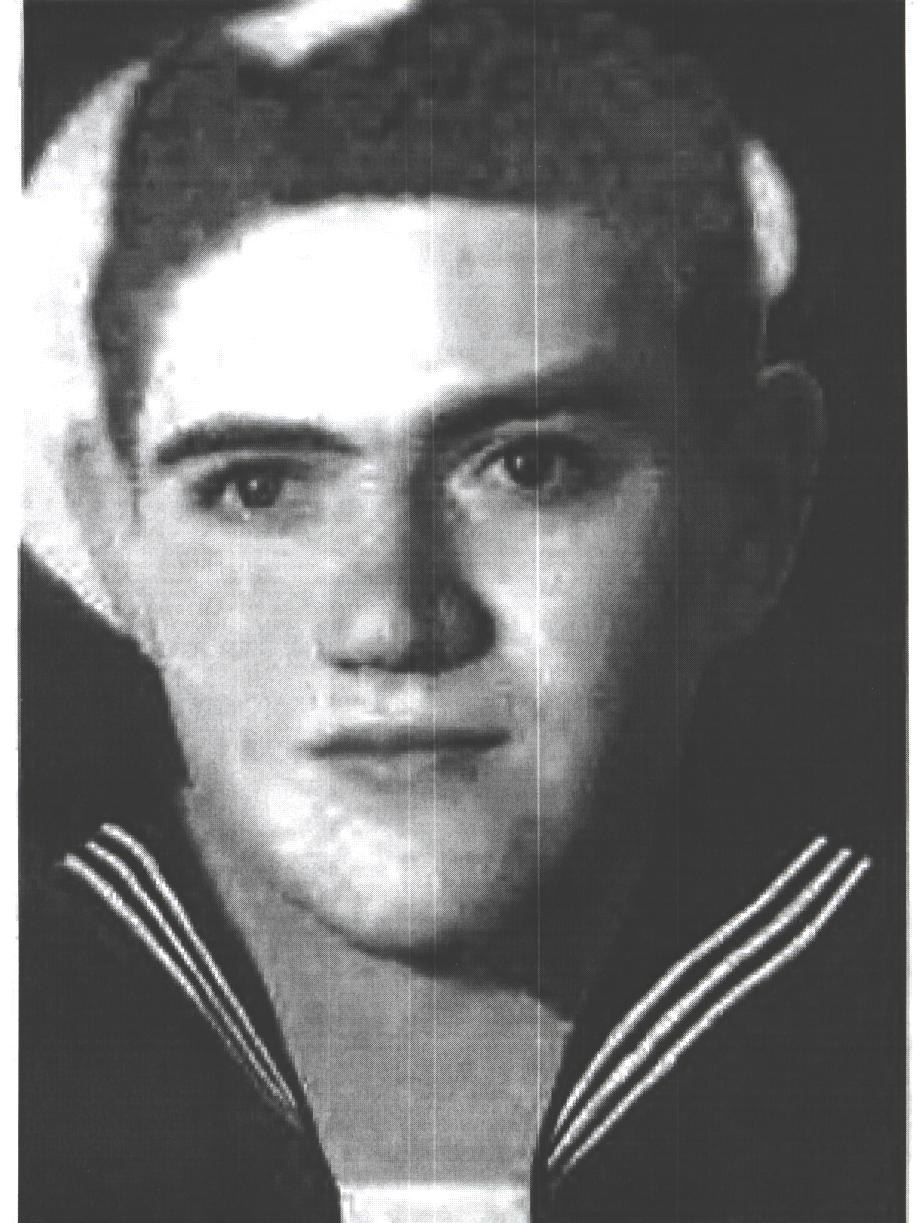

William Hughes US Navy USS Utah |

I had been aboard the USS Utah for more than a year. I had learned my way around that great ship during the first few months aboard as a radio messenger. It is true that I was a lost a great deal of the time. Prior to December 7th I had been promoted from sleeping on a hammock with one of the Deck Divisions to the more luxurious "radio operator" bunk room adjacent to Main Radio. We were located two decks below the main deck, and one deck above the engine room. Life aboard the Utah had been great. I had made the transition from farm boy to the rating of Radioman, third class, and had come to enjoy the cohesiveness of my fellow operators. The operations of the Utah as a bombing target, an AA machine gun school, a submarine target and radio controlled ship was carried out in a disciplined manner; however, our lifestyle was comparatively relaxed. The "chow" was excellent and there was more liberty than we "grunts" could afford. |

Information provided by William Hughes |

But at 07:55 AM, Sunday Morning, December 7th, 1941 our lives would be changed forever. We had not been trained to anticipate a major, all out sneak attack by a large force of foreign military aircraft from a country with whom we were not at war. On that lazy Sunday morning, most off-duty radiomen were asleep on our dry comfortable cots in the bunk room. The tumultuous explosion that rocked the ship almost threw us out of our bunks. We must have been looking at each other in sheer amazement. One man, Radioman 3/c Warren Upton was dressed and "spiffed up" for a day ashore. He was bending over someone's cot attempting to obtain an object from his locker. Another said we had been rammed [by another ship]. Within 20 or so seconds, a second jarring explosion again rocked the ship from the port side, and within a minute the USS Utah was taking on a pronounced list to port. It was obvious to all of us that we needed to reach the top side immediately. As I recall, our departure from the sleeping quarters was orderly but swift. Up two ladders and we found ourselves huddling under a protected part of the superstructure called the starboard air castle. By this time, Jap aircraft were making strafing runs on the hapless sailors who were exposed to their fire. Since all our guns had been covered for bombing practice the week before, we could not fire back, and the giant ship was listing rapidly to port. Personnel who came up from below and entered the deck on the port side were in immediate danger of being crushed from falling timbers, and many were. These timbers protected our deck and provided a viable target for practice bomb hits to be marked when we were participating in bombing exercises. It has been stated that an order to "Abandon Ship" was given. I failed to hear the command above the din of the battle, or, "slaughter" seems more appropriate now. It became a matter of every man for himself. Personally, I felt an urgent need to distance myself from the ship, and a leap over the starboard side fairly early in the game found me swimming to the mooring quay where I was able to hide behind the pilings during the continuing strafing runs. A great danger faced by all of us was jumping on someone in the water, or being jumped on by someone else. Fortunately I was spared from this hazard. At the first lull in activity, I swam for shore, and the only scratch I received during World War 2 occurred when wading up the beech onto Ford Island. I cut my bare foot on a piece of coral. It was minor; it did not delay me from seeking refuge in the pipe line ditch where most of the crew ended up until the planes of our "newly acquired enemy" finally returned to their carriers. There, I "hunkered down" dripping wet in my "skivvy" shirt, shorts and a pair of white knee high tropical trousers. All my personal belongings, including a prized photo of movie actress Rita Hayworth, remained aboard ship in my locker. While hunkered down in the ditch, watching terror reign from the skies, these thoughts: (1 ) Where in the h-- are all these planes coming from and how long will they keep coming, and (2) I asked my nearby shipmates "what do you think "Washington" is going to say about this?" The latter expression stemmed from the fact that I was being trained to copy wireless press news for the ship. For weeks there had been numerous and lengthy press releases datelined "WASHINGTON" with announcements and comments on the world situation. We observed some fine moments.. First and foremost was the heroic action of Warrant Officer Stanley Symanski and the men from the USS Raleigh and Utah, who volunteered to go back aboard the big broad bottom of the now capsized Utah in the face of enemy fire, and cut our Shipmate Jack Vaessen out of the double bottoms. It is gratifying to know that some 59 years later Jack is alive and living in California. So is Warrant Officer Symanski, who retired from the Navy as a Commander. Other personnel exemplified unusual valor in disregarding their safety and operating small boats to ferry personnel from the doomed ship to shore. Others lent a hand to wounded shipmates in distress. It was our worst hour and yet our finest hour. As is eloquently told in the EW reports of Warren Upton and others, most of us ended up aboard the USS Argonne, our Base Force Flag Ship for the night of December 7th. The terrible site of the mangled superstructure of the USS Arizona, the capsized Oklahoma, the sunken California, Nevada, Maryland and other ships, such as the destroyers, Downs and Cassin, and Shaw, the latter three being almost obliterated in Dry-dock, gave us a knot in the pit of our stomachs and very heavy hearts. On the night of December 7th, we brought up ammunition which has been stored in the "bowels" of the Argonne, something new to the manicured nails of a radioman. It would get worse, as we would go back on December 8th and retrieve ammo from inside the Utah, where welders had cut entrances into the bottom. We were the lucky ones, collecting ammunition; many were assigned the job of collecting bodies and body parts from the murky waters of the harbor. Many remains would be buried in unmarked graves. For more information on what has become a "national disgrace" read about the status of many of those graves 59 years later. While aboard the Argonne the night of December 7th. one more shipmate from the Utah, Pallas Brown, Seaman 2nd class would die from a stray bullet fired by our nervous gun crews who were shooting at what they thought was another Jap attack. Unfortunately, they were firing on inbound aircraft from the USS Enterprise which had been given clearance to land on Ford Island. I spent one week aboard the USS Vireo, a mine sweeper, as temporary replacement for their Radioman who was in the Hospital. On December 15th, I was transferred to the USS Saratoga, an Aircraft Carrier, which was destined to be torpedoed in February 1942, but fortunately not sunk. I would serve on other ships being newly commissioned and hurriedly sent to the Pacific where the war was not going well for the U.S. until after the Battle of Midway. The long trek from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay lasted 3 years, 8 months and 25 days. I can truthfully state that I was where it started the day it started, and where it ended the day it ended - although my ship, the USS Gasconade, an Attack Transport, did not drop anchor in Tokyo Bay until 11:00 on Sept. 2, 1945. Alas, the surrender ceremony was over and Navy records do not show Gasconade as being present when the surrender was signed. That long trip was paid for by many American lives as well as lives of our Allies and the Japanese. It is said that the military is only needed when the diplomats fail. Let's hope we keep America militarily strong, the diplomats do not fail and this terrible history will never be repeated. Bill operates a web site honoring the USS Utah at: http://www.members.home.net/wmhughes/visiting.html |