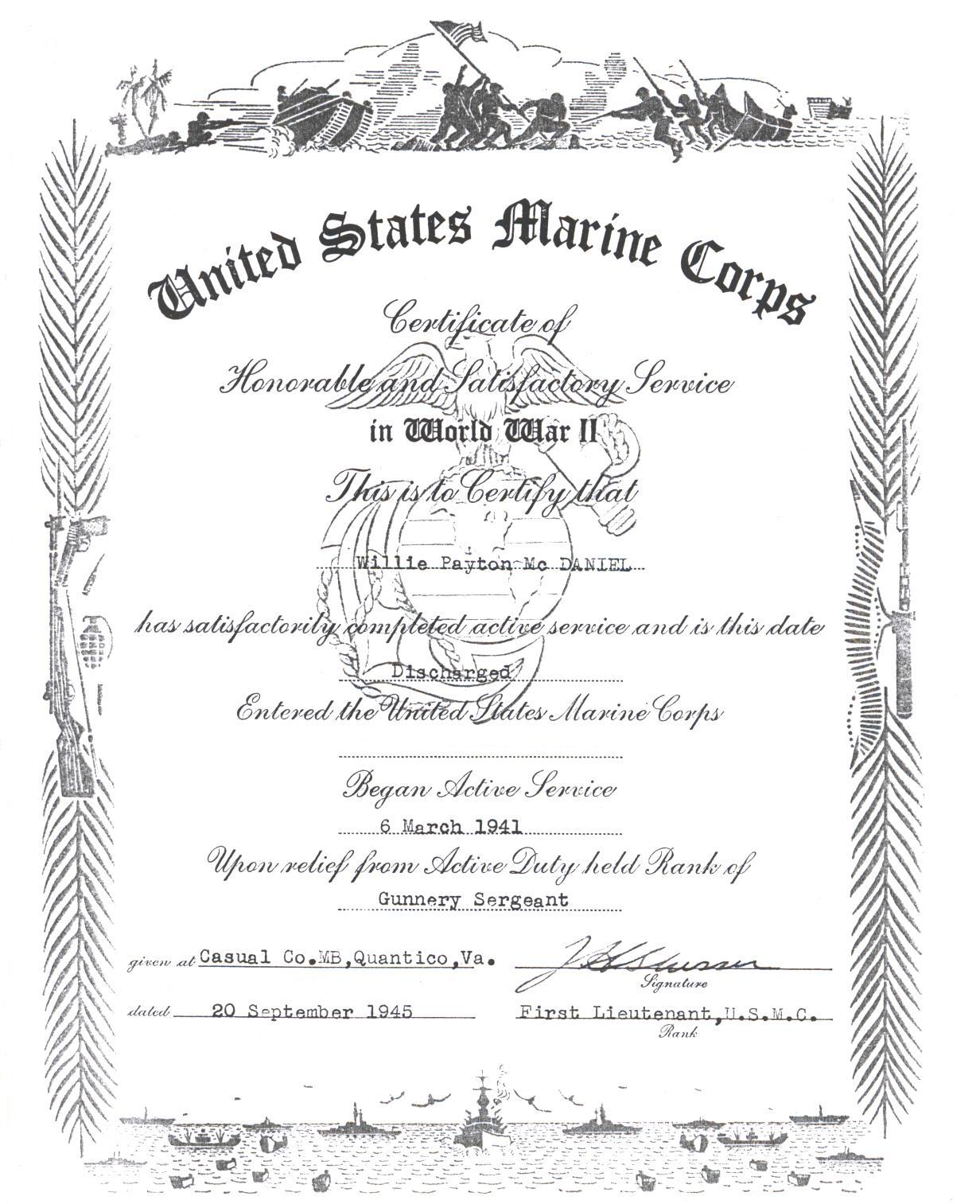

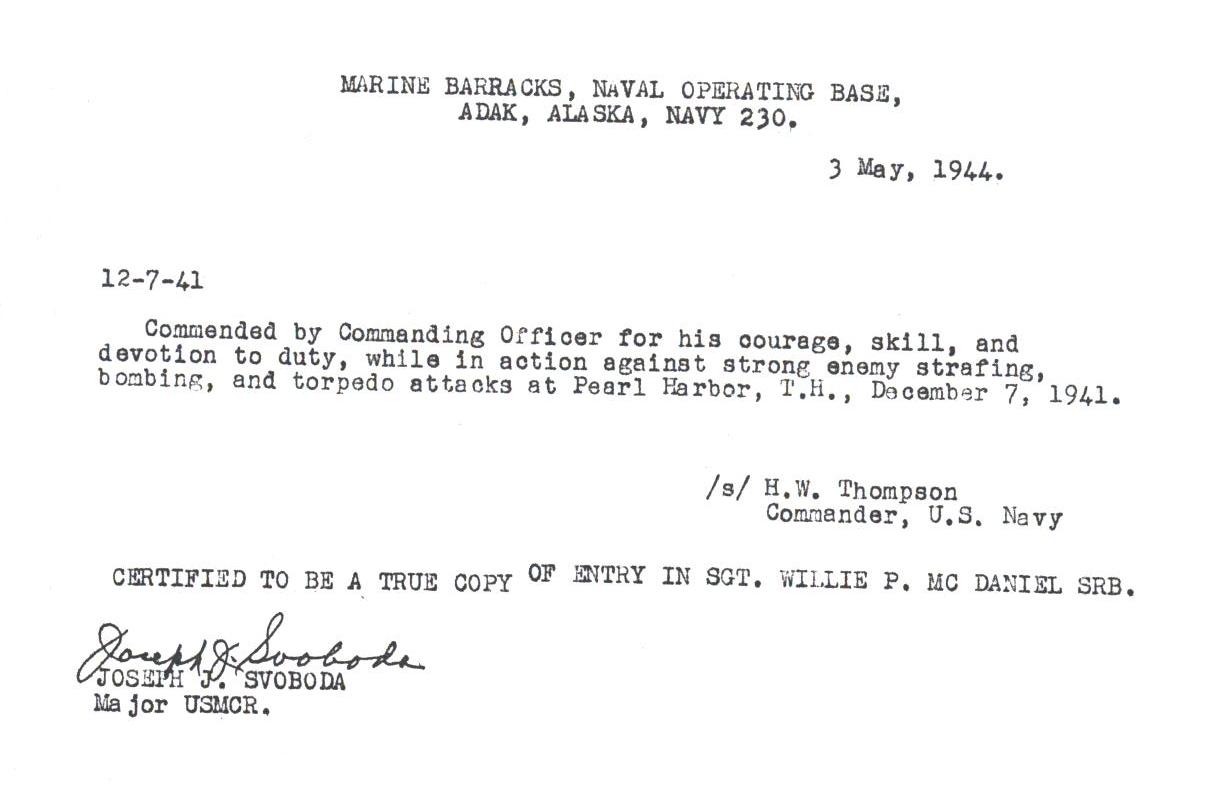

W. P. McDaniel US Marine |

Bill Clothier and I had decided to attend church in Honolulu that morning. We had discovered we both belonged to the same church and were a little embarrassed that we had not attended services since joining the Corps. Bill had his locker in the Marine compartment on the main deck aft just off the weather deck, and I had my locker in gun casemate nine on the galley deck directly above the compartment. From where I stood adjusting my necktie and putting final touches to my tropical khaki uniform, I could see Ford Island directly opposite our quay, and out over the main deck aft to where the color guard was standing with Bugler Mello (USMC) awaiting time for colors. A few other Marines were busy I the casemate as that part of the ship was outboard of the galley, and mess cooks were still cleaning up after breakfast. I could smell the roast turkey, which was to be our Sunday noon fare. The day was bright and calm, and the Harbor was quiet. Outside our casemate on the starboard side of the ship was an ammunition lighter. I am not sure if it was loaded or not. It had been used all day Saturday to remove main battery ammunition from the magazines. Less than fifty yards forward of us was the Arizona, and directly in front of her was the Oklahoma. Aft of us was a large pipeline, I suppose for dredging. Several hundred yards aft and near Ford Island was the old cruiser Baltimore, veteran of Teddy Roosevelt's Great White Fleet. I was told she was used to store torpedoes and mines. Beyond the Baltimore, a Navy hospital ship stood at anchor. On the port side of the ship toward the channel a garbage scow was coming along side, and the boatswain's pipe and voice could be heard giving instructions to the scow and work detail standing by. This was the last moment of peace our County was to know for over four years. The first unusual thing that I heard was the roar of an airplane as it flew low over Ford Island; next came the unmistakable chatter of machine gun fire. Someone made a remark about the stupidity of the Army Air Force firing so near the ships and island. There was still no excitement, and I remember one Marine saying something about the Army using "red dots" on the wings of their planes. I looked out over the island and saw a plane dip low and then pull out, Showing the underside wing markings of the rising sun of Japan. Another burst, much closer, caused the color guard to double time to coffer as splinters ripped from the deck almost at their feet. The seriousness of the situation struck home when I was Mello transport his 240 pounds over the deck at breakneck speed heading for the shelter of the Marine compartment. I do not recall general quarters being sounded. There was no need. Everyone knew something big was happening and where to go. The crew was quiet and reasonably calm though excited as boys might be going to a football field before a game. The battle began with not one battle veteran, so no one as yet knew the extent of the danger, which hovered over us. Since I was a crewmember on gun number nine, I did not need to go anywhere. I was already in the casemate. My job was shell man. I handled five-inch fifty-one shells for the broadside gun. (It is important to note that these shells are not fused, therefore they expose, not by a timing device, but upon contact.) Our gun captain, Corporal Joe Driscoll, arrived and we immediately made ready to fire. A broadside gun will not elevate very far. Its primary purpose id surface engagement where firing at ships or shore targets is possible. The only objects we could train on were very low flying planes. The only chance of damaging one would be a direct hit as the shells only exploded upon striking. It reminded me of trying to shoot a flying sparrow and a .22 rifle. I will never know why, but a t about this time Corporal Driscoll was told over the phone to send pat of his crew to gun eight, directly opposite number nine on the port side. As I recall, two of us were dispatched to Corporal Petersen, gun captain of gun eight. As I entered the casemate, I remember seeing the galley door open and I could see through to the casemate I had just left. I remember thinking how foolish I had been going around by way of a small passageway to get to my new station when I could have taken a shortcut through the galley. Things were really beginning to happen on the port side. Since this gun was toward the Harbor most of the section was visible. Clothier was a member of this crew. I found myself handing powder bags to him. He yelled something about being late for church. The ship was not firing with every weapon. We were firing at anything in the sky. I recall sympathizing with the B-17's I saw coming in for a landing. In the bright morning light, their markings were clear and unmistakable, but very little could be done to protect them as they were in the direct line of fire. The sequence is a little confused, but along about now came the torpedo. The plane came in, dropped low over the water, launched the fish and pulled away exposing his belly to our .50 calibers in the mainmast. We all stopped, calmly walked to the gun port and stared as the little silver streak headed for our bow. I had seen pictures of torpedoes striking ships, and I imagined we would be enveloped in fire and smoke, break in two and sink. As the torpedo disappeared from view, I braced myself and waited. It did not happen at all as I had expected. The ship shuddered slightly, raised a bit listing to starboard, then settled back on an even keel. A plane crashed alongside the dredge pipe aft of the ship. Flames were licking from his motor, and I shall never forget the pilot's frantic struggles to clear his cockpit as it fell. I remember we cheered as he crashed. He later floated face up past the ship. Suddenly someone pulled me from behind the gun. In my excitement, I stepped into the recoil area. The gun would have crushed me to a pulp had it been fired. Then the war became my personal war with a deafening roar. A fragmentation bomb came through the open, glassed skylight of the galley and exposed on the tiled cement deck. Our door into the galley was still open; in fact, we had thrown our empty powder cans into the galley to give us more room. Gun number nine, across from us, had lifted extra powder bags from the cans, so that they might speed up the firing. I do not know how many were exposed, but they all went up in a flash, burning to a crisp those holding or standing near the bags. Shrapnel flew into our casemate, and Corporal Petersen crumpled from a leg wound. Gun eight was undamaged, but gun nine was out of commission. The paint was blistered from the bulkheads, and the gun itself was ripped from the deck. All hands in the area of gun nine were dead or dying with the exception of Driscoll and another man whose name I do not recall. Joe was protected, in part, by the gun itself. His left arm was exposed to shrapnel and was terribly mutilated. The other man was at the shell hoist at the time of the blast, and he was protected. As it turned out later, one other man, Joe Pyper of Salt Lake City, was knocked over the side. Although wounded, he swam to Ford Island. Pyper was reported missing in action and was mourned as the first man lost from Salt Lake. I think it was Christmas Day his family learned he was alive. Things were really getting hot now. Word came from the commanding officer for a crew to man gun six as its crew had been sent to the boat deck to man 5-inch 25 anti-aircraft guns. Again, I was transferred. Upon arriving at gun six, I discovered First-Sergeant Inks sitting on the trainer's stand. The "Top" at his best was a comical appearing little man of the "old Corps". He was short, fat and balding. As I saw him sitting there, had he not been my first sergeant, I would have laughed. He had lost his hat and oil streaked his chubby face and white undershirt. He had a large lump on his head where a beam had smacked him. He had been on the deck directly under the galley hit, and the explosion caused the large "I" beams supporting the galley deck to buckle just enough to rap him soundly on the top of his head. When I found him, he was muttering dejectedly that he would never make it to sea. That was the first indication I had that we were under way. We were moving slowly out alongside the Arizona. Survivors of the starboard crews said later we had just cleared here when the Arizona went up. I guess the Nevada, as a; moving target, attracted the planes over the Harbor. In any event, Inks was right; we did not make it to sea. Five hundred pound bombs exploded on the decks from bow to mainmast. The bridge was enveloped in flames, and the ship began to wind out of control. Her engines were cut, and she lay dead in the water, slowly drifting toward the dry dock area where the Pennsylvania and destroyers Casing, Down and Shaw had been undergoing repair. Some of the bombs dropped by the planes over the Nevada found the floating dry dock and the destroyers, causing an explosion almost as spectacular as the Arizona's (If you will examine the famous picture of this incident, you will see the bow of the Nevada in the lower right hand corner.) As we were sailing down the channel, our guns fired constantly. Our broadside fired round after round directly out over the machine shops and cranes of the repair yard. I was on the pointer stand now and I recall marveling at missing the large hammerhead crane. I fired at a plane directly in line with it, and the projectile must have passed through the maze of steel beams without touching anything. I like to feel, however, that I fired the dud that pierced the brick smoke stack over the large machine shop. These shells were fired in the direction of Honolulu about seven miles distance away. I have often wondered if those were the "bombs" dropped in the city. After the bombs hit out boat deck, the survivors of the gun crews staggered below deck seeking shelter. Corporal G.G. Sweet came into the casemate, followed by two or three sailors. All were horribly burned. Sweet's face and hands were black as carbon. I at first thought it was smoke, but later realized his face and hands were charred black. A sailor moaning in pain was rolling on the deck. Each time his arms or exposed body hit the deck, pieces of skin pealed off. A black sailor had strips of skin hanging from his arms down over his hands in the manner of material from a shredded shirt. At the moment, even with the excitement, I noticed those wearing undershirts were burned only to where the shirt began. Our battle was over for the moment. We were low on ammunition and our targets had left us. I have no idea what time is was. Those on gun six-helped make the wounded comfortable. I administered morphine from the little tube syringes. I had no instructions in this type first aid, but felt I could not do any more damage. Sweet refused treatment insisting he was all right. I remember as he smiled he looked like a colored minstrel with black face and flashing white teeth. (Sweet went on to win a field commission at Iwo Jima.) A large tug (or mine sweep) came along side and slowly pushed the Nevada out of the channel to a spot across the Harbor from the Naval Hospital. Here she settled to the bottom and flooded to her weather decks. All the survivors were told to go to the main deck aft. Our officers told us to arm ourselves. On my way to the rifle rack in the Marine compartment, I went back through my old gun casement where my gear locker was located. Then, for the first time, I was really frightenedwhen I saw those unrecognizable bodies lying grotesquely about the gun, and realizing I was alive only because I had been sent to gun eight. On the blackened gun base was a glass-covered tag listing the gun crew. The name next to the bottom was: WP McDaniel, Pvt., USMC. I had an urge to throw up. Gunny-Sergeant Douglas gave me a push and told me to get sick later, we had work to do. My rifle was not in the rack. Sailors had understandably grabbed any means of protection. They had stripped the rifle rack. It did not matter I did not have any ammunition anyway. My rifle was located several days later under six inches of salt water at the bottom of a whaleboat. I was forced to clean that rifle and recall this being one of the most irritating incidents of the whole episode. Someone did hand me a rifle, and I was given a ration of two rounds. After standing alert hours with loaded rifle, I discovered it to be sans firing pin. Our Marine captain came back to where we were huddled under the number four gun turret and revealed that word had reached her that four or five transports of Japanese had landed on the leeward side of the island. We were to defend our ship as long as possible and then take to the hills. Darkness was not far away, and a detail was sent to the beach to establish a defense line. Some of the Marine survivors went over the side on the line and dug emplacements for our World War I Lewis Machine Guns and Browning Automatic Rifles we had salvaged. (A picture of these emplacements appeared in Life magazine shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. By now, it was a dark moonless night, and something was about to happen that frightened me more than anything that had occurred during the day. The entire ship's crew had not been notified that Marines were in the cane field on the beach. Everyone had been posted and told to be particularly alert for movement on the beach. As I was moving through the tall cane across from the ship's bow, someone from the ship yelled they saw something move. I froze realizing that there were probably five hundred weapons trained in my direction. A small, battery-charged spotlight flicked on and trained up and down the beach. I felt sure if it found me, I was a dead nineteen-year-old Marine. The Marines back aft were also aware of my situation. Word raced forward for everyone to hold fire. I was not assured, and would not move a muscle, until Pvt. Burgess called me by name and told me I could safely return. Thus my battle ended. We fired gallantly at the planes from the Enterprise that night, but we were following orders and could not have known whose planes they were. Sometime during the night, fire broke out on the bow. For years, the ship's fire drills had centered around a fictitious fire in the ship's paint locker. The call was always, "Fire in the paint locker!" Now, there was a fire in the paint locker. I detected a plaintiff note in the voice of the boatswain as he called, "Fire in the paint locker come on fellows, I really mean it!" I have not told all I know happened; I only reported what I actually saw. I did not tell of Gunny Douglas refusing to leave his machine gun platform on the foremast, although the bridge below him was aflame, and the waterlines to his water-cooled guns were shot away. He did not abandon his post until the bullets spiraled through the air like cartwheels, and the guns finally froze. He received the Navy Cross and a warrant. I did not tell of Joe Driscoll winning the Navy Cross by mustering a fire-fighting crew to battle the fire of his own casemate. Although seriously wounded, he directed the fight until he collapsed. I did not tell of hearing the ship's captain, Captain Scandland, say, "My God, what has happened here?" when he came aboard after the battle. I thought of his remark each time I heard heroic statements of the war. His inspiring words will live with me as long as "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" I did not tell of giving my blanket to wrap the body of the Captain's Philippino cabin boy. The blanket was later returned, and I still have it. I did not tell of helping identify Marines by looking for names stamped on fragments of clothing. This was before dog tags for Navy personnel. We found a body wearing a pair of socks bearing the name Pyper. The fact that Pyper was not present, and his name was on the socks caused us to assume he was dead. In true Marine fashion, some poor devil had borrowed a clean pair of socks. I shall never erase from my memory the sight of the rows of broken, burned bodies laid out on the main deck aft awaiting transport to the beach. The dead waited while the wounded were shuttled across the bay to the hospital. I shall never forget the Sergeant Grannel directing obscenities toward the Japanese at the top of his lungs as they carried him down the gangplank to the motor launch. I shall never forget Sergeant Balleau crying when he was told of the death of his friend, Pvt. Keith Smith. I shall never forget Bill Clothier saying that a person of less faith would have qualms about preparing for church again. |

Information provided by Marilyn McDaniel. |