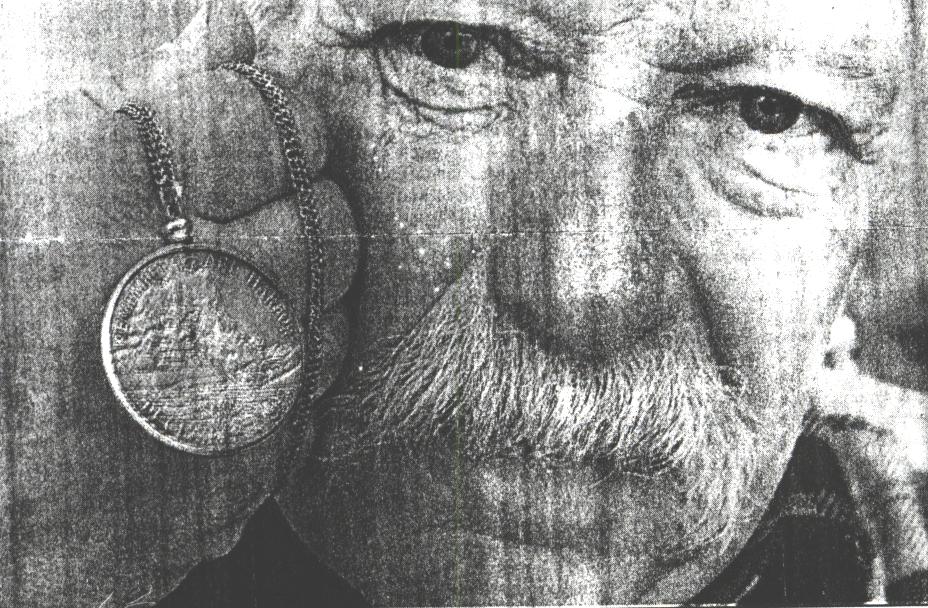

William D. "Bill" Hawes US Navy USS Nevada |

World War II began for Fireman Second Class Bill Hawes when he heard a tapping sound on the battleship deck over his head. "When the attack started, I could hear something tapping on the decklike somebody tapping with a cane. The sound was machine-gun bullets from Japanese airplanes, hitting the deck of the USS Nevada, tied up at a dock 30 or 40 feet behind the battleship Arizona in Pearl Harbor." Hawes was in his quarters one deck below the main deck after breakfast on Sunday morning December 7, 1941. "I never did hear the airplanes before the tapping began". After breakfast, Hawes said he was talking with his friend Jesse James Crabtree. "Old J.J. was from Missouri and we had a lot in common". "This guy came running down the hatch, we both hollered at him to knock off they skylarking, as running was forbidden unless on the way to battle stations." "Skylark, hell," he said, "the Japs've just attacked". And then we knew what the tapping was. Hawes' everyday job was as boat engineer on a 50-foot launch, but his battle station was five decks below the main deck in the forward dynamo, which ran off the ship's steam to make electricity. Hawes and Crabtree reported there, first rousing men asleep in the air compressor room, a compartment adjoining the dynamo. The men slept there because it was their battle station, and at their battle station was the only placer they could get away with sleeping late on a Sunday morning, Hawes said. "We gouged them out and told them we were under attack". Then he and Crabtree went about their duty of closing certain valves and opening others. "You could hear the concussions of the falling bombs and feel them too. After a few minutes, the ship took a bomb or an air-launched torpedo in the next compartment forward. The concussion blew the rivets out of the walls pretty near like machine gun bullets, and one of the rivets went into Crabtree's right thigh. They had already been knocked down and skinned up so many times by the concussions from bombs and torpedoes going off on and near the ship that Crabtree didn't even know he was hit by the rivet. The wound left only a teeny trickle of blood. A while later, they reported back to the main deck to see if they could help man the launch to pick survivors out of the water. "Topside the airplanes were strafing everything that moved and some things that didn't move." "Everybody who was able was shooting. With planes pulling out of dives, the noise was pretty considerable up there." By that time, the Arizona had already exploded and the Nevada was already underway. The ship attempted to maneuver its way out of the harbor to the open sea, where it would have more room to bring its guns to bear on the Japanese airplanes. But Hawes found all the small boats were already manned and gone, so he returned to his original battle station five decks below at the dynamo. When it turned out to be out of commission, Hawes reported to the machine shop, his second battle station. From there, he said, he spent the rest of the battle fighting fires, shoring up bulkheads, and countering floods. The Nevada took most of its bomb hits that day once it got moving. The ship had to move through the harbor without the help of tugboats, and to negotiate its way around a suction dredge which had been dredging the harbor to deepen it. A hose from the dredge stretched a good half way or more across the harbor. The ship, badly damaged especially in the bow, was in the channel leading out to sea when the shooting finally stopped after slightly more than two hours. At that point, somebody in the control tower on land, with a view of the harbor ordered a tog to push us up on the beach on the edge of the canefield so we wouldn't sink. So that's where we were the next time I came topside. We didn't abandon ship at all. When we pushed up on the beach, you could step off the main deck aft in about knee deep water, and step ashore. Out of the Nevada's crew of about 1,200 men, about 60 or 70 were killed that day. And a "great number more than that were wounded. Crabtree's wound was light enough that he wasn't even listed among the wounded. "Crabtree reported to a hospital that day and I never saw him again." |

Information provided by Bill Hawes |