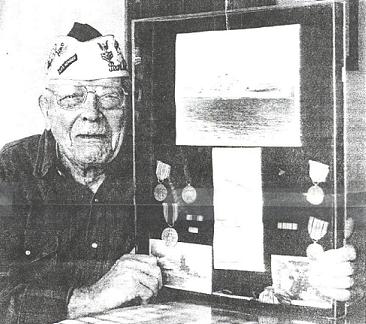

Lawrence Frederiksen US Navy USS Helena |

Machinist's mate First Class Lawrence Frederiksen didn't like the mess hall's coffee, so he had his own coffee pot set up on the ice machine room on board the USS Helena. He was there the morning of December 7, 1941, and it may have been his taste in coffee that saved his life that day. Frederiksen was born near Fort Dodge, but later lived near Livermore. In June 1939, with "nothing to do around here at that time" he joined the US Navy. In 1940, he was assigned to Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, where he was a diesel repairman with duty in the engine room. On that fateful Sunday morning in early December, Frederiksen and a friend a short fellow he called "the Greek" were in the ice machine room having a cup of coffee. Much of the rest of the crew of the USS Helena was in the mess hall having breakfast. At 7:55 a.m., an explosion in the forward engine room rocked the ship. The blast, below the room Frederiksen was in, sent both him and "the Greek" shooting up into the air. "I stood right over where the torpedo hit and I flew right up in the air, Frederiksen said. When he and his companion got back to their feet, "the Greek" said, "Boy, Freddie, they ain't foolin' now." And the Japanese weren't fooling. For almost four hours, torpedoes, bombs and machine gun fire blasted at the ships in the shallow harbor, along with Hickam Air Force Base and Wheeler Field. The USS Helena, in dry dock to be fitted with ammunition, was the first ship hit in the attack. The torpedo to the engine room sent an explosion rolling out over the mess hall next door, knocking sailors over like dominoes. Frederiksen said, "They hit us right at breakfast." "That day at Pearl Harbor, I lost a lot of good friends," said Frederiksen, now a retired farmer living in West Bend. "The only reason I am alive today was because I was in the ice machine room and not standing in line for chow." In the hours that followed, breakfast was the furthest thing from the minds of the men at Pearl Harbor. "I went to my report station and we helped with the wounded and the dead, Frederiksen said. "We never expected anything like that, but we went to our battle stations and helped the best we could." He and others spent hours carrying the wounded from the lower levels of the boat, now sinking to rest on the shallow bottom of the harbor. "We took them off the ship and put them on the ambulances so they could go to the hospital," he said. Though he was below deck for much of the time during the attack, Frederiksen said the scene was not the one of a beautiful sky often depicted in films. The air was filled with smoke, the sky black, and the water seemingly on fire, as the spilled oil and fuel burned throughout the harbor. Men were jumping from burning ships into flame-filled water, and boats attempted to rescue them before they drowned or were burned to death. "We tried to put out the fire, but we couldn't do much," Frederiksen said. The crew of the USS Helena stayed on the crippled ship throughout the day and night, ready in case the Japanese came back. "We were so busy it never really sank in right away," he said. "I never will forget it." In all, eight American battleships and 13 other naval vessels were sunk or badly damaged, almost 200 American aircraft were destroyed, and approximately 3,000 naval and military personnel were killed or wounded, as the attack thrust the United States into the second world war. Pearl Harbor is just one of the sights burned into Frederiksen's mind. Over the next four years, he saw nearly every major battle of the war in the Pacific, missing only Guadalcanal. In January 1942, he went with the then-repaired Helena back to the mainland, where he was transferred to the destroyer base in San Diego and trained to land troops on beaches. He saw action in the Aleutian Islands, the Gilbert Island and many more places throughout the Pacific. Then in 1943, he transferred again and was on a destroyer, finding he way to Enewetak, Tarawa, Okinawa and the Philippines. As August 6, 1945, neared, Frederiksen's ship was one of the hundreds preparing off the shore of Japan for what was expected to be a ground invasion. "I was off the coast the day they dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima," he said. "We jumped up for joyyou would have thought the ship would fall apart with all the screaming." Four years, dozens of battles and countless friends fallen since that day in December 1941. Frederiksen was again part of history. "I fought in the big one, but I was very fortunate to start at Pearl Harbor and go to Japan and never get a scratch," he said. Today, he is part of a rapidly dwindling group of Pearl Harbor survivors. Only about 3,400 men who were there that day are still living. In the last year, five Pearl Harbor veterans have died in Iowa alone. Frederiksen knows the number will continue to decrease, as they all get older. He himself is 83. A member of a Pearl Harbor survivor's organization, years ago he mentioned something he had read about a group of Civil War veterans. The group had bought a bottle of wine, which the last one alive would get, but that survivor had said it was no fun to drink alone. The Iowa Pearl Harbor survivors have their own bottle of wine, but this one is to be shared by the last seven survivors seven for the date of the infamous attack. "We relive some of the battles," Frederiksen says of the group's annual gathering, but the reminiscing is no longer as vivid as it once was, as the years separate that day from the present. Blessed with the fortune of serving throughout the was without any injury, Frederiksen also feels blessed by the life he has had since, and blessed that he has not been haunted by the memories as so many are. "Some guys are still living the war," he said. "I have never dreamed about the war." "I don't forget it, but we don't talk about it much anymore. It gets old." |

Information provided by Lawrence and Irene Frederiksen. |