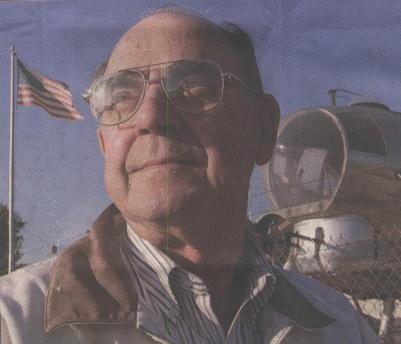

Ernie DiMatteo Hickam Field |

Tulare Advance-Register December 7, 2001 By Rick Elkins It is a day Ernie DiMatteo remembers as if it were yesterday. Now, 60 years to the day since the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, DiMatteo easily recalls what President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called the "Day of Infamy." DiMatteo was stationed at Hickam Field in Hawaii that fateful day when the Japanese attacked, plunging America into World War II. The field is about a quarter of a mile from Pearl Harbor. Today, he can recall in great detail the bombs and bullets landing around him as he and hundreds of other service people scrambled to survive. "It's not something you forget", he said. "It's kind of embedded in our memory". As to why it is important to remember, DiMatteo said, "A lot of men went through a lot of hell." The memory of that day came vividly back to him upon his first visit to Hawaii since he left there in 1944. "I went aboard the USS Arizona Memorial. I didn't think it would bother me. As I looked out, I just relived that morning. I saw the harbor and ships. It all came back to me. I kind of got choked up," he said. DiMatteo, at age 82, still sells vehicles for Sturgeon and Beck Buick, Pontiac and Oldsmobile. He has worked for the dealership for 54 years. On the day of this interview he had just received a letter from former President George Bush commending him for his service and for being a Pearl Harbor survivor. DiMatteo said it was the first such letter he has ever received. He was in aircraft maintenance at the Army Air Corps on December 7, 1941, a day that began much like most other Sunday mornings. "I was in town the night before. I caught the last bus to the base in the wee hours of the morning. I was going to sleep in," he recalled. He had gotten up long enough to have breakfast, then was going to catch up on his sleep when the first explosion was heard. "Everybody looked around and said, 'what the hell was that,'" he remembered. The explosion sent a shock wave that shook the two-story wooden barracks. Someone said the Navy must be doing some dynamiting, then a second bomb went off. Someone then said the Navy must be doing maneuvers, he recalled. About that time the first plane went over the airfield. Nobody noticed the rising sun on the wings of the plane. Jokingly, DiMatteo said it was probably the Japanese attacking. "Here I'm the clown joking the Japanese are here and they were. For the next 45 minutes or so DiMatteo and his fellow servicemen scrambled to stay alive. Up until a week before the attack Hawaii had been on alert. Men were given guns and ammo, told to carry a canteen of water and a gas mask wherever they went. Machine gun nests were set up and planes were loaded with ammo. However, on the morning of December 7, they had nothing. After the attack began at 7:55 am, DiMatteo recalls someone began giving orders for the men to get their canteen, gas mask and .45 caliber revolver, but they had no ammo. A guy went out to the center of the airfield and began giving out the ammo one clip with seven bullets for each man, he said. DiMatteo recalls he quickly decided staying in the open was not a good idea, so he ran for cover. DiMatteo said the first planes came in strafing, then would drop two fragmentation bombs, with the tail gunner strafing the airfield as they left. "One guy had his arm shot off, it was just hanging there by flesh," he said. He remembered that man later had the arm amputated. He said his first thought was to lay flat, since fragmentation bombs send shrapnel upward. "Every time I heard the planes I laid flat. So the bombs didn't scare me, but the strafing when you see the bullets kicking up dirt right in front of your nose, you kind of break out in a cold sweat." One bomb hit close enough to life him off the ground, with a piece of shrapnel striking his let. It was just a flesh wound, one he tended to himself. I'd been ashamed to go to the hospital with a flesh wound. A lot of guys bled to death because they weren't helped quick enough." He moved around, leaving one spot where a few seconds later a man was killed. "I guess someone was looking out for me that day," he said. Following that first attack, about 15 minutes later came the second wave, lasting about another 45 minutes. He recalled a flight of B-17s were just arriving. Many of them were shot down or damaged. The first thing I said was, "I'm starved, where do I eat?" recalled DiMatteo. However, with the base in a shambles, they had to eat outside, and sleep outside for the next several nights. "Rumors were the Japanese were going to land troops. I had one pistol with seven rounds, a rifle with five rounds, a Thompson submachine gun and a shotgun. "I figured if we were invaded we'd shoot until we ran out of ammunition, then we were dead pigeons." They spent the next three or four nights in a trench, but things began to get back to normal in about a week. "We got planes in the air, flying supplies," he recalled. Most planes were lost DiMatteo said they were lined up "like sitting ducks" on the runway. "One plane had 110 shrapnel holes in it." He said they could see the fire and smoke from the harbor, but he never went there to see the destruction the attacks had done. "When you got leave, you went into town to get drunk, not look at damage." He said the most unsettling thing was he could not get word to his mother in Pennsylvania that he was OK. "She didn't know if I was dead or alive." He said they came out to the trenches to take messages for families, but they were never sent. He ran into a friend and had him send the message, "Well and happy." DiMatteo grew up in Pennsylvania. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1930, went through aircraft maintenance school and eventually became a crew chief on a B-24 that ferried supplies and troops all over the South Pacific. With no armament on the plane, DiMatteo said they were lucky to have never run into the enemy. "We just took the risks all the time, hoping we wouldn't get caught." He returned to the States in 1944 for flight training. That brought him to Rankin Field and Tulare. He was going through primary flight training in Bakersfield when the war ended. He figured there was no reason to stay in the military, so he got out of the service and returned to Pennsylvania. "I didn't like the cold. I got in a care and drove out here, stopped in Tulare and stayed. That was 54 years ago November 1947. Information provided by Mary DiMatteo |